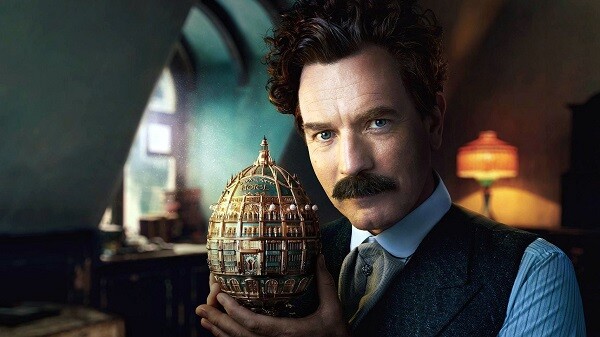

A Gentleman in Moscow, adapted for Paramount+ and Showtime from the 2016 novel by Amor Towles, could be considered as Downton Abbey or The Grand Budapest Hotel meets a Cold War spy tale.

In 1922, Count Alexander Rostov (Ewan McGregor), a deposed aristocrat, is relegated to house arrest in the cramped servants' quarters at the Metropol, a five-star hotel in Moscow, across from the Kremlin. Outside of the hotel, the Russian Revolution continues, as the Soviets consolidate power.

Inside, Alex befriends hotel staff and guests, making the best of a situation designed by the Soviets to lead him to despair. For three decades, Alex not only endures his predicament but perseveres.

How A Gentleman in Moscow Is Like a Russian Nesting Doll

I found the structure of the streaming series strikingly similar to Matryoshka dolls. You probably know them as Russian nesting dolls: wooden dolls where one doll contains another, which contains a smaller one and so on.

The dolls can depict Russian peasant girls, fairy-tale characters, political figure, authors, athletes ... or just about anything.

I own an eight-piece set that’s religiously themed. Seven dolls resemble Mother Mary, and the smallest and eighth wooden doll is the Baby Jesus.

I’ll always remember my late Polish uncle ironically decorating his basement bar with Soviet-leader nesting dolls. Reformer Gorbachev was the biggest doll, with Marx, the originator of socialist/communist misery, the smallest.

A Gentleman in Moscow gives us a bit of both. Each episode considers the Soviet handling of a certain social issue, the system's usual botching of it, and the counter-handing of the same issue by individual characters, who incorporate sacrifice, kindness and generosity.

The key to the show’s theme lies in its title, “gentleman.”

Episodes as Nesting Dolls

Doll 1:

Prince Rostov, the last surviving member of his noble family, begins his home exile in the Moscow hotel. Unlike England, which provided for a dignified transition for their noble class as the country moved towards democracy, the USSR showed little quarter for past rulers.

Even the most harmless of nobles faced house arrest, exile, or, in the case of the ruling Romanov family, execution.

Doll 2:

With the monarchy deposed, Rostov’s friend Mishka (Fehinti Balogun) sings the praises of socialism at a political rally. Rostov reminds him that the problem with economic utopias is that anyone with a good sense about them eventually wakes up from the dream.

For Mishka, this isn’t realized for him until the series’ end.

Doll 3:

Communism is acknowledged at a dinner as a replacement ideology, taking the place where even religion held sway. The novel more precisely and brilliantly covered this topic. See my last *point, below.

Doll 4:

Rostov’s love interest Anna Urbanova (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) acts for a living, mostly at the whim of the Ministry of Culture. For most of the series, she languishes around the hotel, a contrasting nod to the Hollywood movie machine, which, for all its faults, certainly kept its actors working on a more consistent basis.

Doll 5:

Rostov began the story as a mentor to a girl named Nina. Years on, Nina is sent to Siberia, but entrusts her little daughter Sofia (Billie Gadsdon) to Rostov. When cold-hearted Soviet child services attempt to claim the girl, Rostov assumes parentage of her.

Doll 6:

Now-teenage Sofia (Billie’s older real-life sister, Beau Gadsdon) suffers a fall from a hotel stairway. One of Moscow’s best surgeons tends to her successfully, but only because Rostov has a connection and can bypass the overflowing waiting room. The Soviets are shown to lack a basic grasp of triaging.

Doll 7:

Artistic censorship is the final straw before Rostov begins hatching a plan to escape from the hotel. Sofia, now destined to play piano in a traveling conservatory throughout Europe, prepares to play for a gathering of high-ranking Soviet officials.

The hotel manager dictates to her what musical numbers can be played and the tone in which they are to be performed.

Doll 8:

Rostov’s escape from the hotel initiates with dozens of phone calls hitting the hotel at the same time. The plot turns the over-bureaucratized culture against itself, and Rostov slips away unnoticed.

*The Amor Towles novel more accurately portrays the nesting doll structure of the story. A Gentleman in Moscow is the story of a former noble, Prince Rostov exiled in a hotel.

Within that story is the noble discussing with two friends (nicknamed the Triumvirate) the best writers in Russian history. Within that conversation, Dostoevsky is highlighted. Within Dostoevsky’s canon is his best novel, The Brothers’ Karamazov.

Within that novel is the story, “The Grand Inquisitor.” And within that story “Bread” is frequently mentioned as it is in most every major Russian work. Bread has obvious Eucharistic overtones.

So, as much as the Soviet empire tried to bury the Christian faith in Russia, the sacrament was embedded too deep within the culture for the faith to completely disappear.

The trailer is below. Click here for a video summary of the novel, and here for the entire first episode of the series.

Image: Paramount+/Showtime

Click here to visit Father Vince Kuna’s IMDB page.

Recent posts:

The Best Things Are Free: Roku’s Family & Kids Hidden Gems

Faith & Family News: 'The Chosen' S4 Sets Streaming Date

'Wildcat,' Flannery O'Connor and the Holy Spirit

'IF': Cute, Feel-Good Tale Explores Fatherhood and Imagination

Keep up with Family Theater Productions on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.